Moses Freeman

Old news clipping of Tom West

Vintage Brainerd High water fountain

James Sears in front of Brainerd

Greg Walton

Billy Von Schaaf

Side of Brainerd High auditorium

Mid-century windows of Brainerd High

Ray Coleman

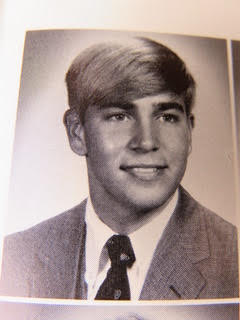

David Everett as a student

David Everett

As an energetic black civil rights activist just a few years out of college, Moses Freeman had his hand on the pulse of Chattanooga’s racial relations, particularly as it involved young people.

For starters, the Chattanooga city councilman from 2013-2017 had taught at Howard High School into 1969 before leaving prior to the end of the school year to work for Chattanooga Progress Inc.

under John Dyer.

In his new position, which deliberately was filled during the school year to prevent a teacher from holding it just during the summer and returning to teaching in the fall, he helped write grants for Chattanooga. It was an office that would eventually fall under the city.

He had also been involved at that time with a group called the Black Activists, which, with the help of the Rev. John Bonner of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, had met with 30 local white leaders and then on their own with 30 local black leaders.

Amid all that work, he remembered being the commencement speaker at Notre Dame High School in 1969, and also talking with students in classes. Notre Dame, while mostly white, had been a leader in Chattanooga in integrating its school.

He also recalled going to Central High on Dodds Avenue in the spring of 1969 with his group after the school had some racially related problems.

While Central did not have the issues related to the playing of “Dixie” or the use of the Confederate flag as a school symbol, as did Brainerd High, the school did have the more universal problems of the time. That included black youngsters wanting more of the opportunities they thought they were supposed to get with the passage of civil rights and voting rights acts, as well as blacks and whites learning to get along together in school.

“We had gone into Central and met with the faculty and tried to reduce the racial tension and instructed the teachers how to deal with black students,” Mr. Freeman recalled in a telephone interview.

But despite all that, he was not involved when the biggest racially related school crisis to hit Chattanooga occurred at Brainerd High School over black student wishes that the Confederate flag and the playing of “Dixie” be dropped.

Reportedly as more of a Southern heritage reason without sensitively looking at larger society as would be done today, the then-all-white school had chosen the Rebels nickname in the early 1960s.

And to many of the later students, all the adornments represented simply a love for Brainerd High School. Although, most from that era would say that varying levels of racial prejudice likely existed, just as similar feelings did throughout many parts of the country.

Mr. Freeman said that black leaders like James Mapp of the NAACP and the Rev. Robert Walton of Rose of Sharon Baptist Church were involved in the fight, due to family, as was administrator Dr. C.C. Bond from the Chattanooga city schools office.

As a result, Mr. Freeman did not feel the desire to be involved at Brainerd as he normally was.

“I never was at the school,” he said. “I wish I had been involved just because I was involved in everything. But I thought the situation was well under hand.”

Mr. Freeman, who at the time lived not far from Brainerd High among mostly white neighbors, did remember hearing reports of various fights at the school, and that the black students were told not to go into restrooms by themselves.

The whites also remember learning how to avoid fights.

Although the issues of prejudice, racial sensitivity and Southern and even school heritage were quite old in Chattanooga and American history, handling confrontations at Brainerd seemed to be a new experience for everyone.

And that included the school leaders who were likely caught off guard when blacks started to skip pep rallies because “Dixie” was played, and a fight broke out in the stands at the Riverside-Brainerd game on Oct. 3 over efforts to damage a Rebel flag.

David Everett, a white senior at Brainerd that year and a member of the Student Council, remembers that early on, the school board tried to intervene, but he thought they did not handle the situation right.

“They had us sit black and white side by side in a meeting in the library run by the city school board,” he recalled. “And they said this is what you are going to do about it.

“If they had kept the school board out of it and taken the student leaders of the school and said, ‘You all figure it out,’ that would have been much better.”

He said that from years of coaching youth baseball, he has realized that youngsters will get together and do what is right and just whenever a crisis situation – like a questionable umpire call -- comes up.

Tom West, a white football standout and senior that year, also agrees that the situation did not seem to be handled well. He recalled that whenever a racially related fight would break out at school, officials would simply cancel classes for the rest of the day.

Instead of attempting the hard task of curing a deep-seeded illness called racial divide, they would simply treat a symptom.

“They made a lot of mistakes,” said Mr. West, who, like Mr. Everett, had no animosity against the black students and was just trying to keep the school together as a senior student leader. “Fights would break out and they would close the school down. That just sent everybody outside and it was a real mess.”

Mr. Everett seems to remember that school might have been closed down for the day eight or nine times over the course of that school year, even into the spring. As a result, he and other students worried if that would affect their academic standing toward going to college. However, school officials assured them they would not be negatively impacted.

As all this unrest continued, whites would parade around the Brainerd area with Rebel flags for a period, despite a brief curfew. Mr. Everett believes 80 to 90 percent of them had no connection to Brainerd High. They were just supportive of the larger and varying issues the Confederate flag represented to them.

A person from another school at the time recalled in an email that Confederate flags could also be seen by students at other white or mostly white schools at sporting events or on cars during those months.

While many of the white student leaders who were not really involved in the protests felt somewhat helpless in getting the situation resolved, so, too, did some of the black students in getting their wishes met.

James Sears, a black senior that year, said the black students who were wanting “Dixie” to quit being played as a Brainerd fight song and the Confederate flag removed as a school symbol felt like their requests were falling on deaf ears.

“We would try to have meetings and go to the school board, but nothing prevailed,” he said. “They would listen to us at the school board meetings and nothing happened.”

The principal, Ray Coleman, probably felt like he was between a rock and a hard place trying to solve the very disruptive issue in an apparently fair manner, as about all the students were upset or negatively affected in some way.

In February 1970, as various protests and disturbances continued to break out at the school, he left Brainerd to coordinate urban education with the city central office.

While the various factors in the move were not known, he was called well loved in an entry in the 1970 school yearbook, the Heritage.

“With his unfailing effort to involve all students in all aspects of school life, he will always be one of the ‘unforgettables’ to those who were fortunate enough to be at Brainerd during his time,” the tribute said.

He was replaced as principal by Dr. Billy Von Schaaf, who came from Dalewood Junior High.

Mr. Everett, who played on the tennis team and had originally wanted to be a baseball player, said he liked Mr. Coleman, who had been the successful football coach in Brainerd High’s early years. But he did see a difference in the two principals.

“They were two totally different leaders,” he said. “For me, Mr. Coleman was very low key and had a lot of empathy for us as individuals but was very stern. He had a way of getting a point across by looking at you.

“Dr. Von Schaaf had German ancestry. He was much more stern. And maybe at that point and time, that was needed. But maybe with Mr. Coleman things would have been just as good.”

Greg Walton, a black football player and junior that year, recalled with a laugh that Dr. Von Schaaf was not afraid to use the paddle.

Mr. Walton added that a lot of the changes at Brainerd came because a number of black students began enrolling there from Howard and Riverside, and they were perhaps used to focusing on more black-centric issues.

Mr. West recalled that the black and white students had gotten along well a few years earlier at Dalewood Junior High during those early days of integration.

Mr. Freeman added that while he was on the periphery of what was going on at Brainerd, he knows it did play a big role in the eventual replacement of another education leader. That was Dean Petersen, the Chattanooga health and education commissioner.

While Commissioner Petersen, a former Central football coach, was a respected educator and public elected servant in the eyes of many, Mr. Freeman said some blacks began to think that he was not responsive enough to the Brainerd crisis.

And that was at a time when Ralph Kelley, the young former Chattanooga mayor who many saw as quite progressive toward blacks and might have tried to help the Brainerd situation more, had just left to become a federal bankruptcy judge.

As a result of the lack of perceived sensitivity, the local black community began eyeing Commissioner Petersen’s seat. And in 1971 educator John Franklin was able to become the first black elected to the City Commission in a citywide vote.

It was a seminal moment in Chattanooga civil rights history, and Mr. Freeman thinks it had its birth in what took place at North Moore Road beginning in the fall of 1969.

“We took on Dean Petersen because of what he had done at Brainerd,” Mr. Freeman said.

* * * * *

Note to Readers: As this series begins to wind down with likely only one or two more entries, readers are welcome to email to the address below any memories they have of the incidents at Brainerd High in the 1969-70 school year. Especially welcome are memories from both any female students at the time and former students who fervently waved flags or fought changes that fall.

* * * * *

To see the previous entry in this series, read here.

https://www.chattanoogan.com/2019/9/14/396257/John-Shearer-The-Brainerd-High-Crisis.aspx

* * * * *

jcshearer2@comcast.net