Early phone operator at the Tennessee Electric Power Company

Parkway Towers building

photo by John Shearer

Parkway Towers building

photo by John Shearer

Parkway Towers building

photo by John Shearer

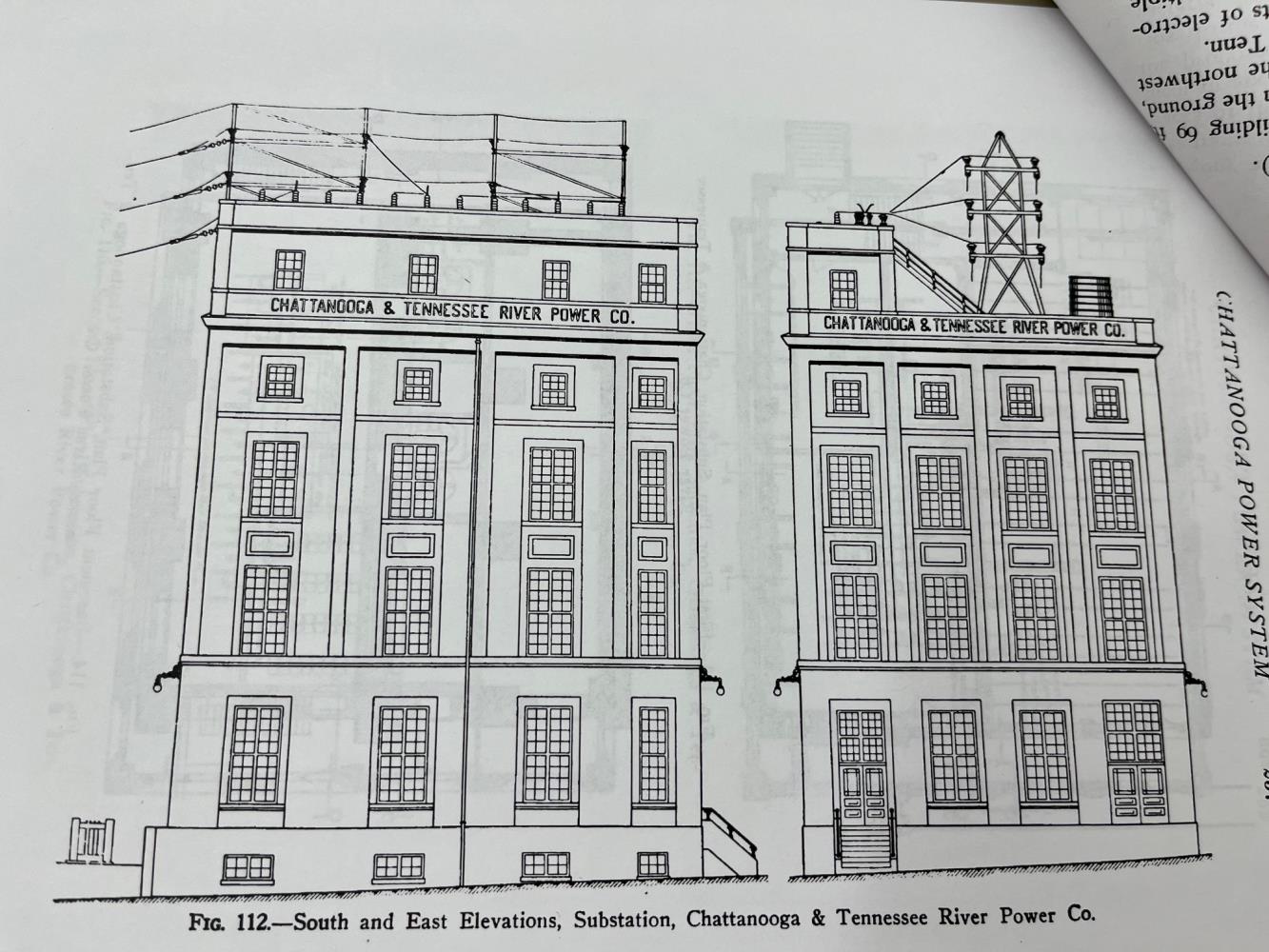

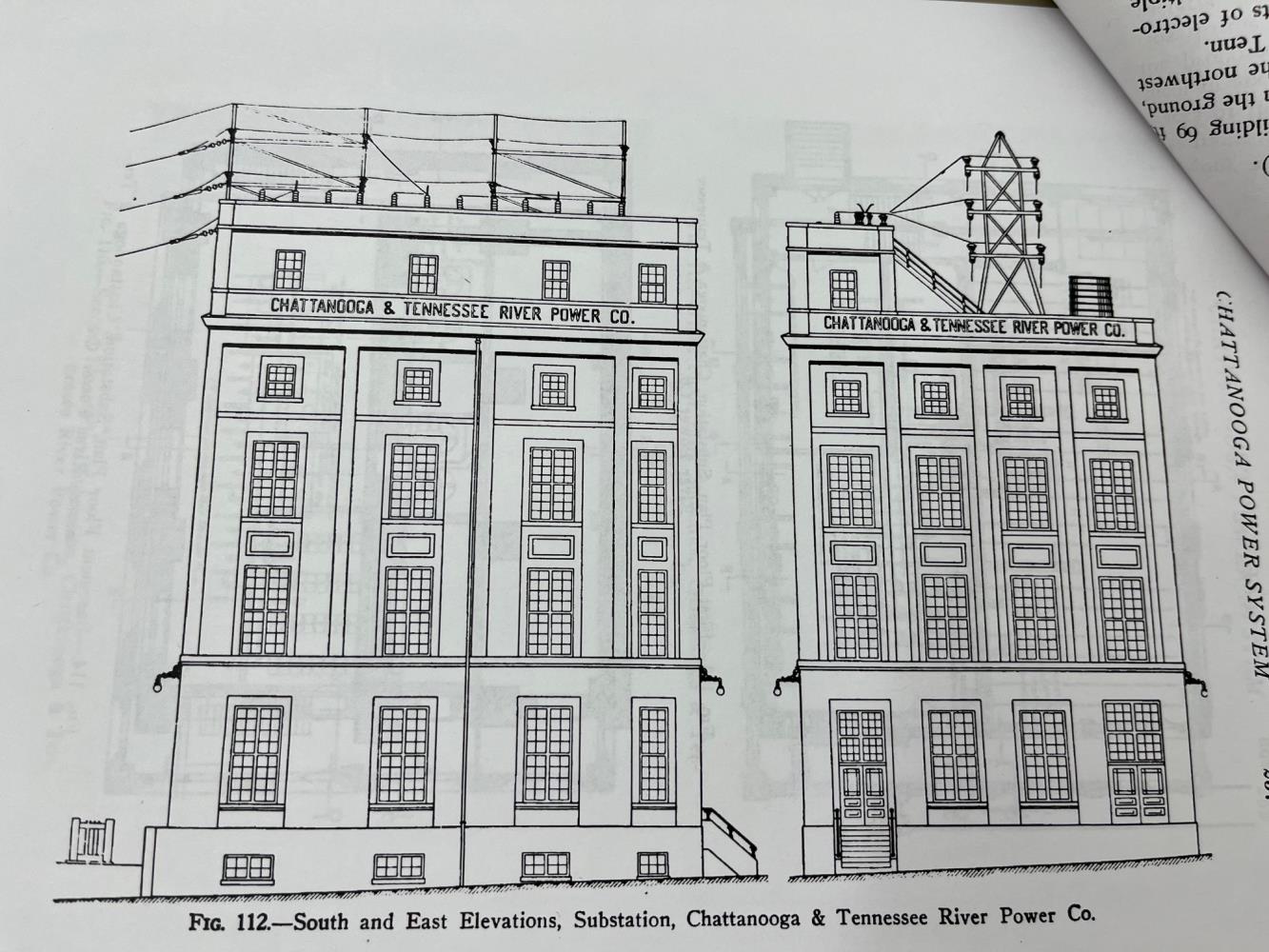

Early drawings of current Parkway Towers building

photo by John Shearer

Early drawings of current Parkway Towers building

photo by John Shearer

A recent inquiry on the history of the Parkway Towers building – which was a former power substation structure – got the Chattanooga Public Library’s Jennifer Rydell burning her own research energy to find additional information.

What resulted after I had already written one story that included some general information was the discovery of some old newspaper articles that give additional background into the beginning of this long-unused structure. The building has been in the news recently after property owner Maurice Kadosh of KH Property Group said it might be preserved as part of a condominium development.

The new information discovered pinpoints when construction began and even who designed and built the structure. Part of a project of the private Chattanooga & Tennessee River Power Co. involved in the construction of Hales Bar Dam, its construction had begun on April 20, 1909, according to a Chattanooga Daily Times article.

“Engineers will stake out the lines of the building, and a force of men will begin excavating for the foundations,” said the article of the building that at the time was said to be at the corner of Carter and Henry (later 19th) streets but now has an address of 1823 Reggie White Blvd.

The article said the building was to be of reinforced concrete with a steel frame. The concrete work was being done by the firm of Schillinger Bros. of Chicago under the direction of Howard Eggleston of Chattanooga, and the steel frame was to be erected by the locally based Converse Bridge Co.

Byron T. Burt, the general manager of the Chattanooga & Tennessee River Power Co., said in the story that he thought the building of the “transformer house,” as it was then called, could be completed and roofed within 60 days. It was to connect with the dam some 17.5 miles away, and work on the transmission lines was also already underway.

Mr. Burt also said a contract with the Alabama Great Southern Railroad had also been signed for the laying of switches leading up to the building.

A follow-up article in the early August 1909 Times said that most of the steel work on the building by then had been completed, and that about all that remained was to erect the lightning arrester house covering about half of the roof (and visible today).

“Into this will come all of the cables that carry the current from the powerhouse at the lock and dam, and here will be located machines, which, in the event of the currents becoming too heavy because the cables have been too heavily charged by lightning, will burn out and so prevent the passage of the current down into the building and the consequent damage therefrom,” the article said in trying to describe the function in layman’s terms.

The August 1909 article also said that the concrete walls of the building were up beyond the second story, and nearly all the conduits had been placed in position.

A May 27, 1913, Chattanooga Times article also found and written about six months before the dam was to begin operating and producing power said that the Chattanooga powerhouse building had a capacity of 40,000 volts of power. It contained the transformers for lowering the voltage to 4,000 and 2,300 volts and allowing the power to be distributed to individual power users.

That article also said the Hales Bar Dam powerhouse (which looks like a longer version of the Chattanooga one), the transformer house, the substation, the transmission lines and all the electrical work were designed by Thomas E. Murray, a consulting engineer for the company.

So, the Parkway Towers building was apparently designed for function over form, although the structure does give an interesting look at the style of the architecture of power-related buildings at that time.

Mr. Murray in an also-discovered 1910 professional article titled “Electric Power Plants” tried to describe what was inside the building.

In a mostly scientific paper, he said that the power came through copper connections on the third (or top) floor. It then ran down to the second floor and went through a circuit breaker before going down to the first floor, where some large step-down transformers were as the voltage was reduced.

He said there were two transmission copper lines that came into the building from the dam via towers on concrete foundations. The lines also crossed the Tennessee River twice.

Some further research would be required to see if the towers are still standing amid the additional ones TVA constructed over the Chattanooga region a few decades later.

The day the power was turned on after Hales Bar Dam was completed was Nov. 13, 1913. One can only imagine the excitement felt among the company officials and general citizenry when the electricity reached all the way to the Chattanooga building. It was likely a powerful moment in more ways than one.

Mr. Murray’s life story might be more interesting to read than his scientific descriptions, as he had worked with Thomas Edison and developed power plants in New York City. He was also an accomplished inventor before his death in 1929 and is credited with such patents as the dimmer switch and the screw-in fuse.

The whole Chattanooga area project with which Mr. Murray had been involved had been started by the Chattanooga & Tennessee River Power Co. and officials Josephus Conn Guild Sr., Signal Mountain developer Charles E. James, and New York investor Anthony Brady. It was formed as a business to aid navigation of a rough stretch of the Tennessee River and create private power. The inspiration had come from an idea launched a few years earlier by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and official Dan Kingman, whom Mr. Guild Sr. knew.

In 1922, the Chattanooga & Tennessee River Power Co. merged with a company that had also been trying to create power from the Ocoee River, and the newly formed company was called the Tennessee Electric Power Co. By then, Jo Conn Guild Jr., the son of one of the founders, headed the firm.

In early 1924, TEPCO’s new eight-story building at Sixth and Market streets was opened. Designed by architect Charles Bearden and constructed by Mark Wilson company, it featured the first four floors as TEPCO office and display space. The top four floors were leased out as offices, and a newspaper article said this area was considered sought-after office space.

The building was later taken over by the Electric Power Board, a non-profit and independent utility board created by the city of Chattanooga in 1935 after area power became a public entity with the creation of TVA. Founded through an act of the Tennessee legislature in what was a period of public vs. private debate that went all the way to the Supreme Court, EPB’s purpose initially was to distribute electricity provided by TVA.

EPB used the Sixth and Market streets building for decades. But after a new EPB headquarters by M.L. King Jr. Boulevard opened in 2006, the building was torn down in 2008 by building owner Unum. The razing had come after a futile period of Unum working with River City Company to find a new use for the site. The lot is currently a parking lot.

But the Parkway Towers building – which EPB disposed of and sold several years ago after also continuing to use it as a substation – still remains, as does the Hales Bar Dam powerhouse. The dam, on the other hand, had leaking issues and was replaced by the Nickajack Dam in 1967 as TVA was expanding the locks of its dams. Hales Bar Dam was largely dismantled, although some pieces of equipment were used in the Nickajack Dam.

The Parkway Towers building, which developers hope to investigate further regarding its possibility for preservation, also is still considered a tangible example of the early days of electrical – and financial – power.

* * *

Jcshearer2@comcast.net