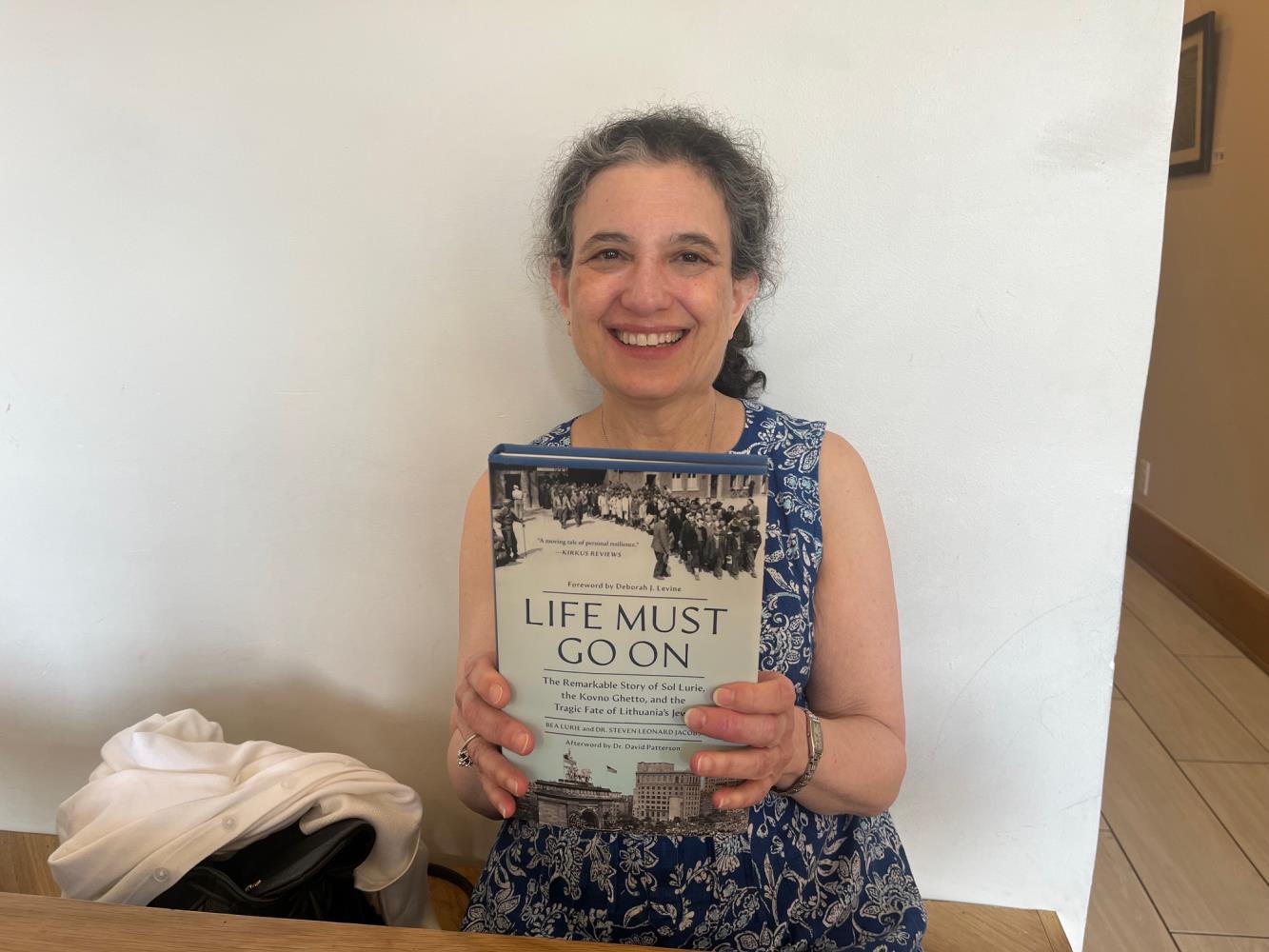

Bea Lurie with book

photo by John Shearer

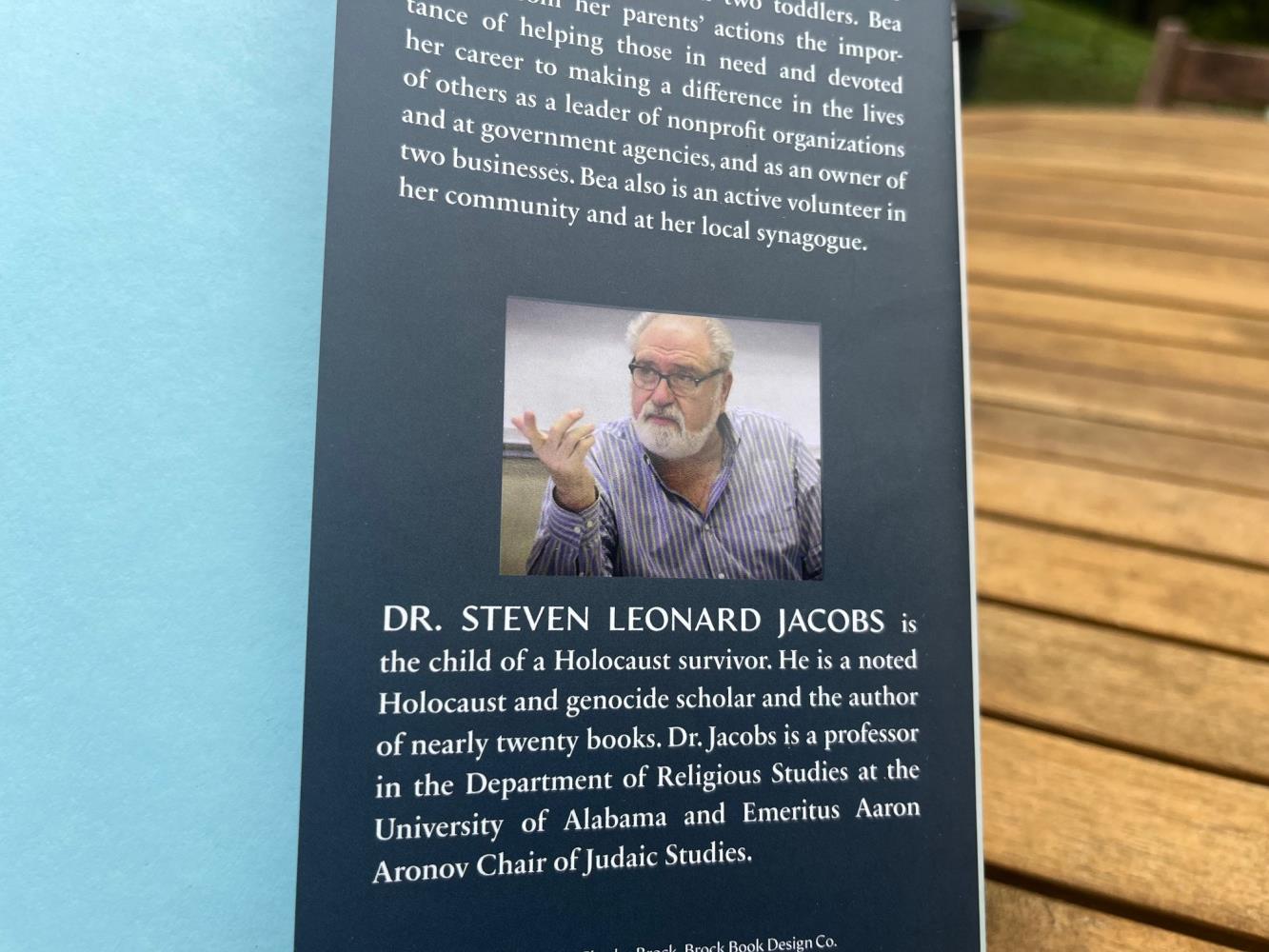

Dr. Steven L. Jacobs on book jacket

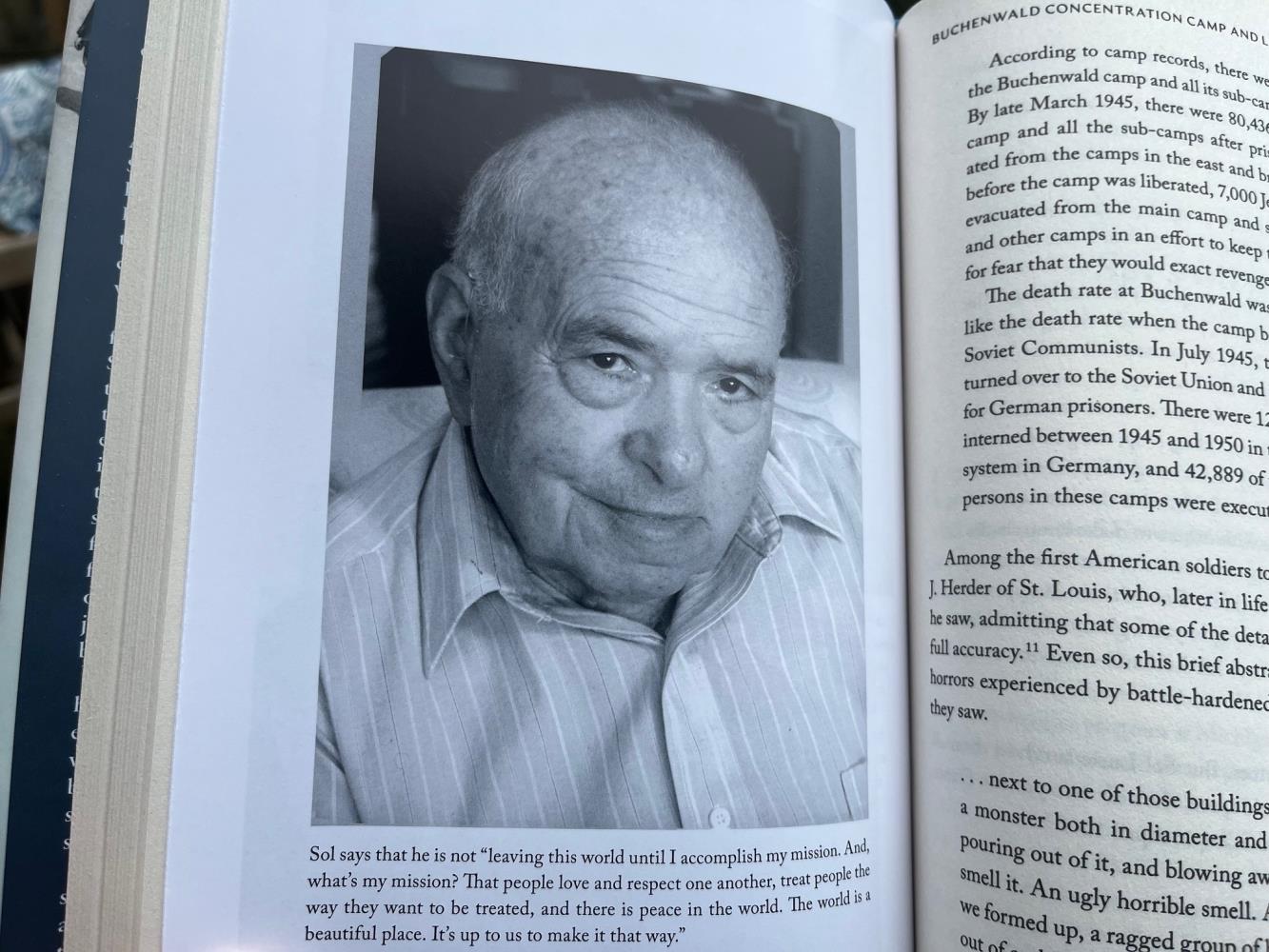

Sol Lurie photo in book

Chattanoogan Bea Lurie has co-written a book about her father’s survival while in captivity as a young man during the Holocaust, and his subsequent life that also brought additional moments of overcoming.

But the main theme might be that Sol Lurie not only escaped death under Adolf Hitler’s cruel Nazi regime of World War II, but that he also evaded having a negative outlook or losing hope on life in general.

"He was a fighter,” Ms. Lurie proudly said during a recent interview at Rembrandt’s regarding her new book, “Life Must Go On,” which she co-wrote with University of Alabama Holocaust and genocide historian Dr. Steven Leonard Jacobs. “He grew up in a family where he was expected to do that. And he was just determined he was going to outlive Hitler.”

Ms. Lurie hinted that not only has her father had a long journey of twists and turns, so also did the book.

As is chronicled, Mr. Lurie had come from a deeply rooted Lithuanian Jewish family, who had enjoyed a comfortable life. But that all changed dramatically when he was 11, and the Nazis invaded his country. His family was forced to live in the Kovno Ghetto, which later became a concentration camp.

The Germans had invaded Lithuania one day before his grandfather died in June 1941, and then he had to travel with his family deeper into Russia. But a Nazi soldier almost for some kind and unexpected reason told them to take another road, and that ended up saving their lives before they arrived at Kovno, Ms. Lurie writes.

She also tells of her father hiding “like a rat” in holes and building walls during the day in the ghetto while his parents worked slave labor, and being taken to the Dachau concentration camp in a boxcar and sprayed with DDT as a cruel Nazi form of being disinfected.

Other memories include only getting two slices of often moldy bread a day and having to sleep on his side with numerous other children on primitive bedding and no blankets.

He somehow and almost miraculously survived all the torment of this time along with his brothers and father and was freed on his 15th birthday. As Ms. Lurie summarizes in the book, the last place of captivity was at Buchenwald, and he had an emotional moment when he started looking out at the woods and seeing a tank and soon realizing it was an American tank. He was to be free and no longer had to wear a striped uniform!

His mother, however, had unfortunately died during the Holocaust.

After the war, he moved to New York to be near relatives, and he also served in the Korean War for his new country and eventually married a fellow Holocaust survivor, Evelyn. As he built a place in America, he later worked for a paint store in what was then a rough neighborhood of Brooklyn before taking over the business.

His daughter recalled that robberies were common at that time, and he used to keep his money in separate pockets and give any robbers money just from one. He later took over that business and had a cookie route in the South Bronx and survived robbery attempts there as well.

“He had so much luck,” said Ms. Lurie, who moved to Chattanooga to live in 2002 after her husband, David Eichenthal, was named as then-Mayor Bob Corker’s internal auditor before he worked with the Ochs Center and in policy consulting. “In his mid-50s, he retired and had enough savings to live well.”

Despite all that he had overcome dating back to the trauma of the Holocaust as a Jew and avoiding being one of six million to perish, he had not completely overcome the mental captivity over what had happened to him as a child.

“He didn’t tell me anything until I was 44,” she said. “My father, like many Holocaust survivors, thought that nobody wanted to hear about what he went through. He clearly had PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), but nobody knew what PTSD was. He didn’t go to therapy.

“And my mother never told us anything, either, except when she got angry after we didn’t eat our vegetables,” Ms. Lurie continued with a laugh. “She said that we were ungrateful, that all she ever had to eat (under Nazi imprisonment) were potato peels and sewer water and some occasional bread.

“She died in 1993 never having shared what happened. My uncle had wanted her to share but she didn’t.”

As a child, Ms. Lurie said it was also hard trying to grasp what her parents had gone through, and she suffered somewhat as well. She remembered trying to find out about the Holocaust by going to the library when she was about 10 or 11 but having no one at home with whom to talk about her discoveries.

Eventually, though, about 20 or 25 years ago, her father started opening up about his experiences. And he did it in a big way, as he started going to schools and other places and began sharing with youngsters the atrocities he had suffered. He would find the sense of respect he would receive at these engagements much different from his youthful days of horror.

“These kids would race up to him afterward and want to meet him,” she said. “He really had a huge impact.”

He also spoke in Chattanooga, and someone at that time encouraged Ms. Lurie to write a book about her father’s life. By then, he had encouraged his daughter to document his journey.

However, it was not easy even for her to recount those events vicariously, and she admittedly had to take a break. “I got to Chapter 3, and I couldn’t write anymore,” she explained. “It is so hard to imagine another human being so cruel.”

The book was eventually completed, though, and published by Pegasus Books. Ms. Lurie provides the anecdotal and factual stories of her father intermixed with historical information by Dr. Jacobs about the Holocaust and places where the elder Mr. Lurie was imprisoned. It is a part of the Holocaust story that has not been chronicled in as much detail.

Dr. Jacobs, a professor of religious studies at Alabama and the author of nearly 40 books, said in an email interview that he considers Mr. Lurie’s story fascinating. “Having had the privilege of spending three days with Sol early on, it was a rewarding and enriching experience for me as the child of a survivor myself,” he said.

He added that his story is also a tribute to the human capacity to overcome the worst and make a better and more positive tomorrow.

Ms. Lurie, the former Girls Inc. CEO who is now the development director for Preserve Chattanooga and welcomes speaking opportunities about the new book, said writing it has also been cathartic for her and given her a sense of hope, too.

That is in part because her father, although always optimistic that good fortune would follow him, has become more openly loving in more recent years, she added.

“I wouldn’t learn from my father if he didn’t have hope,” she said.

Sol Lurie, who is now 95, lives in New Jersey and in recent years has suffered from dementia-related health issues. But he is excited to know about the publication of the book and has not lost his joyful attitude and hope for the world, in part because he remembers several Germans helping him while he was imprisoned, she added.

“He really believes that if we can figure out how to learn not to hate, we can make the world a beautiful place to live,” she said.

And that includes being aware of the past and the horrors of the Holocaust at a time when many believe the world is again becoming more authoritarian amid claims of rising attacks on personal freedoms, she said.

As Dr. Jacobs added similarly, “We need to learn from this darkness of the past as a warning to the present and future to be on guard as to not repeat these tragedies but to more fully be aware of the conditions that bring them about.”

* * *

Jcshearer2@comcast.net